Second Offering: The Negro Side of 1619

Today’s offering asks us to open our eyes and reclaim the practice of solidarity and resistance epitomized by the Negro antiquarian

How does a people know who they are? How do they even know they are a people?

Catch up on the first offering here:

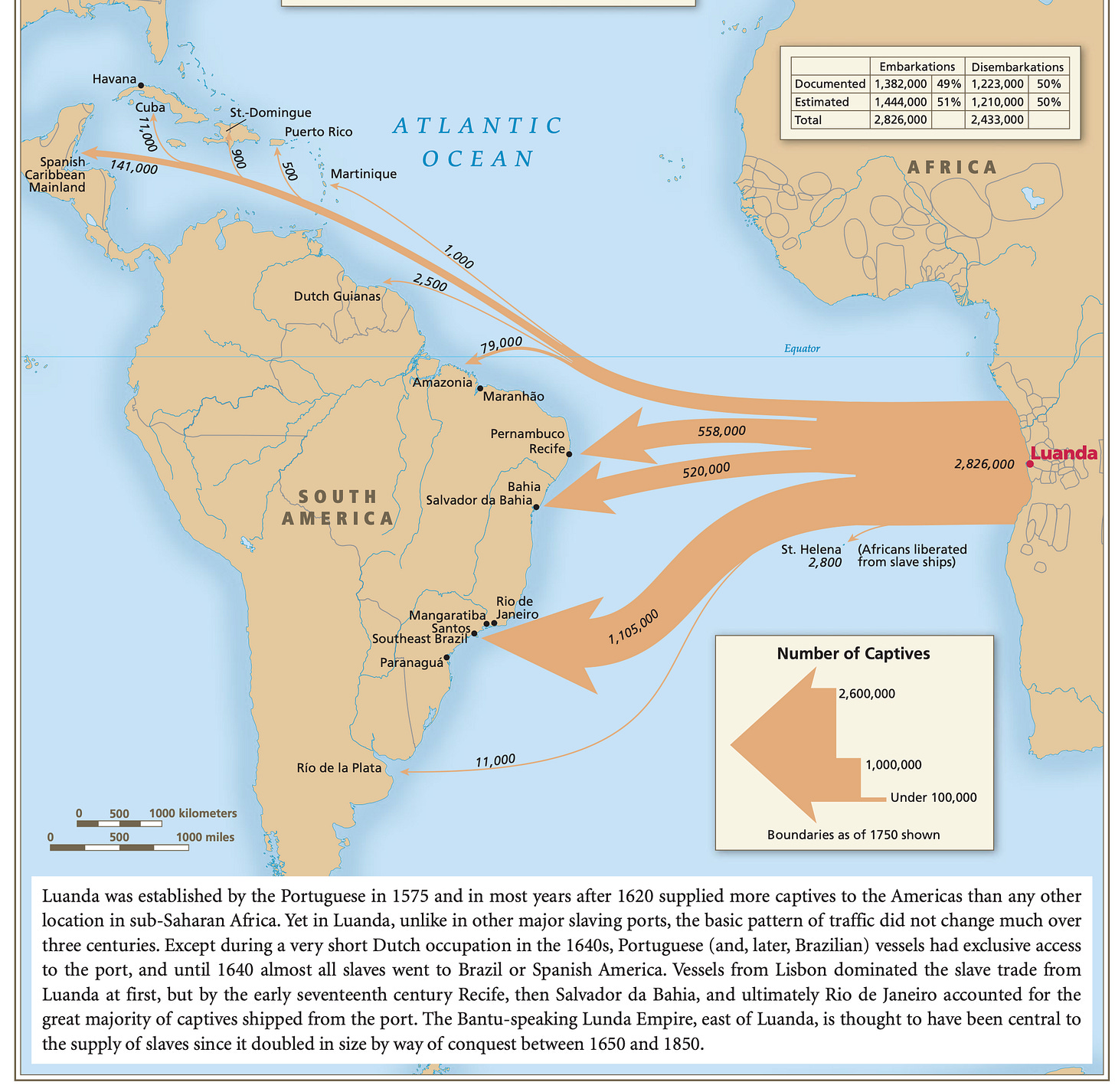

So after the Mendes de Vasconçelos men, father and son, orchestrated the slaughter of hundreds and trafficking of thousands of women, children and men for the pleasure of the Portuguese king, these subjects of the kingdoms of Ndongo, Matemba, Angola, and Kongo were taken on ships from the port of Luanda to parts around the world.

In the maps of slave ships we have available to us today, visualizations of data collected from slave ship registers, travel accounts, colonial documents, and the hands and minds of trusted researchers, we would still never know that some of those Africans leaving from Luanda, in 1619, on a Portuguese slave ship named São João Bautista, would end up at Point Comfort, miles off the Portuguese captain’s course in a swampy outpost off the coast of Virginia, a place now called Fort Monroe.

In 1619, the São João Bautista left the coast of Africa near Luanda flying the Portuguese flag and on its way to Vera Cruz. The Portuguese had hold of the asiento by then, giving them a license to take and take and take souls onto ships and land them in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Brazil for slave traders and colonial administrators alike to purchase. The Spanish thought it unseemly and against their Catholic pearl-clutching morals to traffic in human bondage directly. Thanks in part to Friar Bartolomé de las Casas petitions (another “man of his time”), the asiento now covered the sin. The Spanish would not traffic in slaves. They would simply license the right to other nations and purchase from those who did. I guess they were leaving it up to the slave traders to defend their own souls once they reached the pearly gates.

How much the asiento mattered to the Kongo, Angola, Ndongo, Imbangala, Kimbundu, Vili and other women, children and men roiling in the depths of the hold we can never know. Global contracts for forced and carceral labor often seem strange and opaque to the average of us, busy going about our everyday lives feeding, watering, and caring for our families, our homes, our communities. But somewhere a cabal of nobles, explorers, and mariners decided that the asiento gave them the cover they needed to get rich quick, and they were willing to do anything to join the fray. They had little oversight. They didn’t wear masks, show their badge numbers, have body cams, and were rarely reported or upbraided for their behavior. Sometimes, like in the case of a woman “big with child” and known only as “No. 83,” they let their frustrations out in a depraved and sociopathic manner. No. 83 suffered the abuse of crew member who took her “down into the room and lay with her brute-like in view of the whole quarter deck.” Such violence verged on damaging the merchandise. The captain punished the crew member, proving that, sometimes, if it threatened the profit margin, a rape could be witnessed, even avenged.1 Sometimes. Rarely.

The cabal of nobles, explorers and mariners who developed a taste for slave trading, a fraternity not unlike the fraternity of men revealed in the Epstein files, did not necessarily need to be from the same country. In fact, by the time the São João Bautista hit the high seas, the English and the Dutch had decided they wouldn’t be left out of such bloody good fun. Attacking under subterfuge, false flags, and with plans for glory, God and gold (or sugar, the white gold of the early modern era), privateers took the São João Bautista at sea. Two ships did the deed: The Treasurer and The White Lion.

The crew of these ships proceeded to divide the Kongo, Angolan, Ndongo, Kimbundu, Imbangala, Vili and more women, children, and men between them( only fair after all). And they headed back out to sea, searching for a likely British colony to “bid em in” and buy them all.

How does a people know they are 20 Odd Negroes? From Angolan to Negro, from African kingdom to Virgina Company, from warrior to slave to servant, all it took was...

….well, it took a lot. It took force of arms. It took political subterfuge. It took Portuguese alliances and lies and hubris. It took English privateers willing to troll the ocean looking for black gold. It took a ship that needed to resupply and was willing to trade water and food for bodies. It took a company official to write it all down. A clerk to save the document. A royal official to save the document. An archivist to preserve it. A researcher to return to the archive and ask, when they came across it all, “well what do we have here?”

A whole slave ship auction wasn’t necessary for Africans to land at Point Comfort. Just white slavers needing water. But the caprice of circumstance masks the global, generational effort of making people into property. Of attempting to tear people from their people.

What I mean to say is: Europeans fought with every military, political, technological and intellectual tool in their belt to make an empire of slaves because people know they are not property, humans know they are not things, the living know they are not dead. Europeans fought to create empire, and it remains an unfinished fight, one they had and have to wake up and defend with bloody purpose every hour of every day for generations.

No wonder they are so fucking mad right now. I’d be mad after centuries of trying and failing at supremacy too.

Because they did fail. And continue to fail.

Those “20 odd” didn’t relinquish their identities easily, didn’t become just Odd and Negro and a number in an archival document. As late as 1667, John Johnson, Jr., the grandson of “Antonio a Negro,” one of the captives on that ship, owned a homestead on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and named it “Angola.” Black man, born on black earth in Virginia, child of Black people who lived the time of slavery by refusing erasure, as we have since 1444, since 1502, since 1619.

Refusing erasure is an act of claiming kinship and peoplehood and John Jr. did—he claimed himself and his grandfather and a land across the ocean. The West Central Africans who stepped off The White Lion did so as survivors of a hard and dark time but would go on to carve comfort at Point Comfort, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, and beyond, a labor of care and claim of power.2

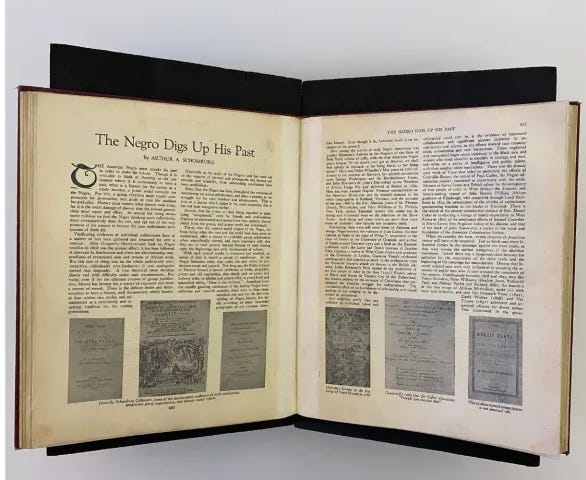

In 1925, the year before Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of African American Life and History christened the first Negro History Week, Black Puerto Rican scholar Arturo Alfonso Schomburg wrote “the American negro must remake his past in order to make his future.” Born in San Mateo de Cangrejos, Puerto Rico, in 1874 (two years before Woodson), a town created by maroons absconding from Spanish predations across the Caribbean, Schomburg would eventually migrate to New York City and become the curator of Division of Negro Literature and Art at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library. In 1972, the collection would become the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and under director Howard Dodson would open a new building with expanded purpose.3

Schomburg did not shy away from the word Negro, did not shirk from Anglicizing or Latinizing his name (using Arthur and Arturo throughout his life). He did not seem to have much interest in policing the lines of Blackness, diaspora, slave or immigrant, nation or even identity. Why should he? He was a man of his times and his times told him that to be Black is to be rigorous, global, transnational, and multi-lingual. To be Black is to be the child of Africans dragged from their homes to foreign lands by strangers seeking greed and gold.

The documents we take for granted today? Phillis Wheatley’s poems, Equiano’s testimony, Jupiter Harmon’s sermons, Paul Cuffee’s petitions and more? at the time of Schomburg’s writing, those papers had been long ignored by white professional historians. To be Black is to name your home for your grand-parents struggle and to name your struggle by building an archive and gathering with other “Negro antiquarians” fighting to recover narrative material written by Africans and their descendants, the residue of textual resistance enacted by Black people in the United States, Caribbean, and African continent.

For Schomburg, to be Negro was to be at the most violent intersection of slave and immigrant, so that the words for either elide into a shared language of exploitation, extraction, and empire. Slave, immigrant, African, Black, to be Negro was to know these mattered only in what fierce history we recovered and retaught ourselves, mattered only in how they fueled our solidarities and fight against empire.

To succumb to the terms placed upon our beings is to allow our histories, our identities, creativity, and sense of ourselves to continue to be guided, routed, and manipulated by white people who dream of pledging the conquistador-settler fraternity that gave birth to Ep Phi Stein.

“The Negro has been a man without a history because he has been considered a man without a worthy culture. But a new notion of the cultural attainment and potentialities of the African stocks has recently come about. Already the Negro sees himself against a reclaimed background, in a perspective that will give pride and self-respect ampe scope, and make history yield for him the same values that the treasured past of any people affords.”

Today’s offering asks us to reclaim the practice of solidarity and resistance epitomized by the Negro antiquarian himself, the descendant of fugitives, the defiant Antilliano, the son of Harlem, who knew our kinship mattered more than our differences because our differences were created by men with guns, men on ships, men with rape in their eyes. He knew that the lesson of history and the lesson of community and the lesson of solidarity are a Venn diagram and that diagram is a circle.

Happy 100th Black History Month to all. Happy 101st birthday to this incredible essay. Mr. Schomburg, ibae! We speak your name.

Readings

Arthur A. Schomburg, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” in The New Negro: An Interpretation, ed. Alain Locke (Albert and Charles Boni, 1925). (READ)

Biplob Kumar Das, “ICE’s Private Prison Contractors Spent Millions Lobbying to Force Banks to Give Them Loans,” The Intercept, February 5, 2026, https://theintercept.com/2026/02/05/private-prison-corecivic-geo-group-ice-bank-loan/;

Associated Press, “‘Negro’ Will No Longer Be Used on US Census Surveys,” TheGrio, February 25, 2013, https://thegrio.com/2013/02/25/negro-will-no-longer-be-used-on-us-census-surveys/

D’Vera Cohn, “Race and the Census: The ‘Negro’ Controversy,” Pew Research Center, January 21, 2010, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2010/01/21/race-and-the-census-the-negro-controversy/.

Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross, A Black Women’s History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2020).

Sylviane A. Diouf, Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America (Oxford University Press, 2007).

“A Look at Arturo Schomburg’s Essay, ‘The Negro Digs Up His Past,’ 100 Years Later,” The New York Public Library, accessed February 6, 2026, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2025/03/04/look-arturo-schomburgs-essay-negro-digs-his-past-100-years-later

“1924: A Year in the Life of Future Schomburg Center Founder Arturo Schomburg,” The New York Public Library, accessed February 6, 2026, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2024/01/03/1924-year-life-future-schomburg-center-founder-arturo-schomburg

Resources

“In 2000, respondents were allowed to pick more than one race for the first time. The “race” data item retained essentially the same categories as in 1990 with a few adjustments. “Black or Negro” became “Black, African Am., or Negro” marking the first appearance of “African-American” on the Census form. The three Native American categories were grouped together as “American Indian or Alaska Native” with a write-in of tribe. “Guamanian” became “Guamanian or Chamorro” and “Hawaiian” became “Native Hawaiian”. The “Other API” group was split into “Other Asian” and “Other Pacific Islander” with a separate write-in. Finally, “Other” became “Some other race” with its own write-in line.”

And:

““In the 2000 census, about 50,000 people specifically wrote in the word Negro when asked how they wished to be identified. By 2010, unpublished census data provided to the AP show that number had declined to roughly 36,000.””

Also— Fort Monroe, National Park Service site: https://www.nps.gov/articles/featured_stories_fomr.htm

Annual Arturo A. Schomburg Lecture and Conversation, directed by Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, 2025, 01:27:27,

This is offering #2 of Stitch Open My Eyes a 12-week community offering on history and memory in slavery’s archive. Because the Black freedom struggle during slavery should be a topic of conversation at every kitchen table. Follow along by subscribing below.

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning I get a commission if you decide to make a purchase through my links, at no cost to you.

June 1754, on the ship of Captain John Newton as described in Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross, A Black Women’s History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2020).

We see this among the survivors of the Clotilde two centuries later. Sylviane A. Diouf, Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Center opening reported in Afro American, October 11, 1980. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=tSkmAAAAIBAJ&dq=schomburg%20center&pg=6299%2C1405282

🙌❤️🔥